Chehabism

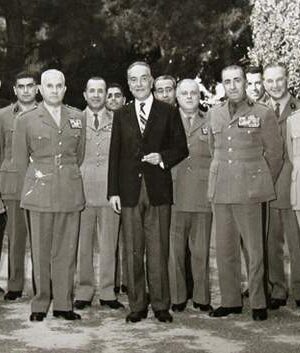

What is 'Chehabism'

The word ‘Chehabism’ was used for the first time by Georges Naccache (renowned journalist and minister) in his famous lecture “Un Nouveau Style – Le Chéhabisme”, in November 1960. When this term became commonly used by the media to refer to Fouad Chehab’s style of governance, Chehab personally downplayed any philosophical or ideological attribute to it, and simply stated that, his, was a way of governing that aimed to serve best the Lebanese entity by constantly taking into consideration its various components’ needs and particularities. Chehab believed that with the implementation of adequate administrative reforms and long-term nation-wide development projects, the State would be strengthened and would thus provide the best guarantee for a better and more stable future for the Nation.

To successfully accomplish such a deed, Chehab’s approach was to move cautiously but steadily. He knew from his leadership experience as Commander of the Army that any adventurous step in a confessional context as delicate as Lebanon’s, would bring counter-effects in the long run. His actions were based on thorough planning, never on impulsive decisions. He wanted the mind-set of the people to evolve with conviction, along with the changes at the institutional level.

Chehabism is, thus, the particular approach to governance, adopted by Fouad Chehab, and the public reforms linked to it.

Objectives of Chehabism

Fouad Chehab did not seek power; he even repeatedly declined the presidential post:

– In 1952, when he was named Prime Minister to oversee the presidential elections and was proposed as a candidate;

– In 1958, when first approached, as the emergency of the situation was pushing him forth;

– In 1960, when he presented his resignation;

– In 1964, when he refused to allow the constitution to be amended for him to run for a new mandate; and again in 1970, when he explained in a realistic and noteworthy statement his reasons for not running for the post.

When he was elected in 1958, Chehab’s mission was clear: To stop the violence, diffuse the tensions and restore harmony in the country. As successful steps were materializing in this primary task, Chehab’s second endeavor started taking shape: Bringing about reforms that would strengthen the State’s apparatus and make it the true reference for all citizens, establishing thus the true ‘State of Independence’ as he dearly called it. In his eyes, this would free citizens from feudal and confessional dependence, foster national unity and build a strong immunity against possible future crisis.

The Chehabist thinking, conceived state reforms as going hand in hand with social and economic nation-wide urban and rural development. True social justice meant that development should reach all parts of the country – especially the most deprived areas – , and all segments of society.

This long-term strategy was the goal and purpose of Chehab’s governance model. Political games, power seeking and adversities based on sectarian interests, were not a dynamism that Chehab looked for or fed on. He viewed these practices, as diversions and distractions from the main and higher goal.

The end-results of the Chehabist mandate were highly successful: Taking over an almost collapsing country in 1958, President Chehab, over six-year later, was handing a stable nation, with all sectarian tensions appeased, citizens re-united, important reforms and development projects underway, all this promising a future of harmony and economic prosperity.

Fouad Chehab Personality Traits

Chehabism is intimately linked to Fouad Chehab as a person, and to his personality traits. He was neither a politician by nature nor by intention. He was above all a man of values and principles.

As an army officer shaped by the French military tradition, he belonged to a school of discipline, nobility, ethics and professionalism. There is no doubt that he embraced, with a deeply rooted conviction, the principles and values of the French Republic democratic culture, and was strongly influenced by it.

As a commander and builder of the Lebanese Army, he inspired immense respect, not only for his strict enforcement of discipline and conscientious application of rules, but also for his empathy with and genuine caring for his subordinates, for whom he was a fatherly figure.

As a Christian, he was a faithful believer and a compassionate person, applying his religious principles and moral values to his personal life and his pubic conduct. Detached from worldly materialistic attractions, he accomplished his duties free from personal interests, and lived a life of contentment sparing a regular amount of his simple salary (30%) to discretely support people in need. His mature Christian faith made him respect all other religions equally and keep a positive disposition for inter-religious faith dialogue.

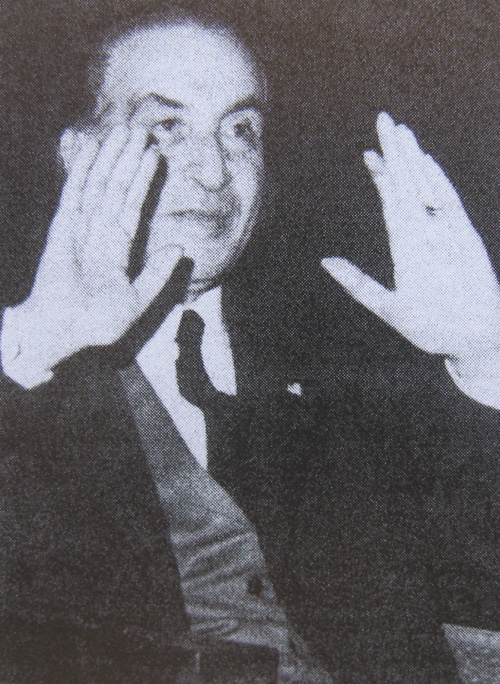

As a person, he was modest and humble, full of goodness and empathy. His life-style was extremely simple, even austere (which earned him the nickname of ‘hermit’ or secluded). His best friend and confident was his wife, with whom he shared the same beliefs and philosophical values. They shared a dislike for social life and outings, and the same hobby of reading and discussing books on politics, history and spirituality. Books were the only gifts that he would accept and appreciate.

As an interlocutor, he was an exceptionally good listener. He was very courteous, of refined manners, and spoke calmly and clearly. His words and thoughts were balanced, never imposing or aggressive, rather aiming to convince. His transparent sincerity inspired trust and respect in people who met him. (This was probably a determining factor in gaining Nasser’s trust during their cornerstone 1959 summit on the Lebanese-Syrian border.) He was discreet and reserved on matters that were not of public concern. His beliefs were clearly expressed in the yearly Independence Day speeches to the Nation.

Before taking action with regard to his public responsibilities, he gave ample time to study the subject matter at hand in details and asked for expert opinions, especially on issues that were not familiar to him. He was realistic in his assessments and his choices of actions, which were often based on healthy common sense. He was far-sighted in his planning. He had a subtle understanding of human nature and awareness of its weaknesses; and therefore had no illusions regarding the Lebanese common citizen and his/her capacity for change from being individualistic to prioritizing public interest.

He was the only Lebanese statesman to bring social concern to the same level of political concerns, and to work diligently on all social issues. He was completely dedicated to his work, spending his private time studying files and holding meetings to ensure the effective execution of all plans (His heavy work schedule and resulting tension made him lose 17 kg during the 6 years of his mandate).

He was not interested in enjoying the extravagant privileges that come with authority and power. He never traveled abroad during his mandate. He viewed his presidency role as a mission, and treated it as a duty and service towards the people of his country. In this, he actually was the contrast of traditional politicians usually driven by power ambitions and personal gain. His public appearances were restricted to the annual official occasions like the Independence Day. He strongly disliked appearing in the media or using any kind of propaganda. His approach was to work effectively yet silently.

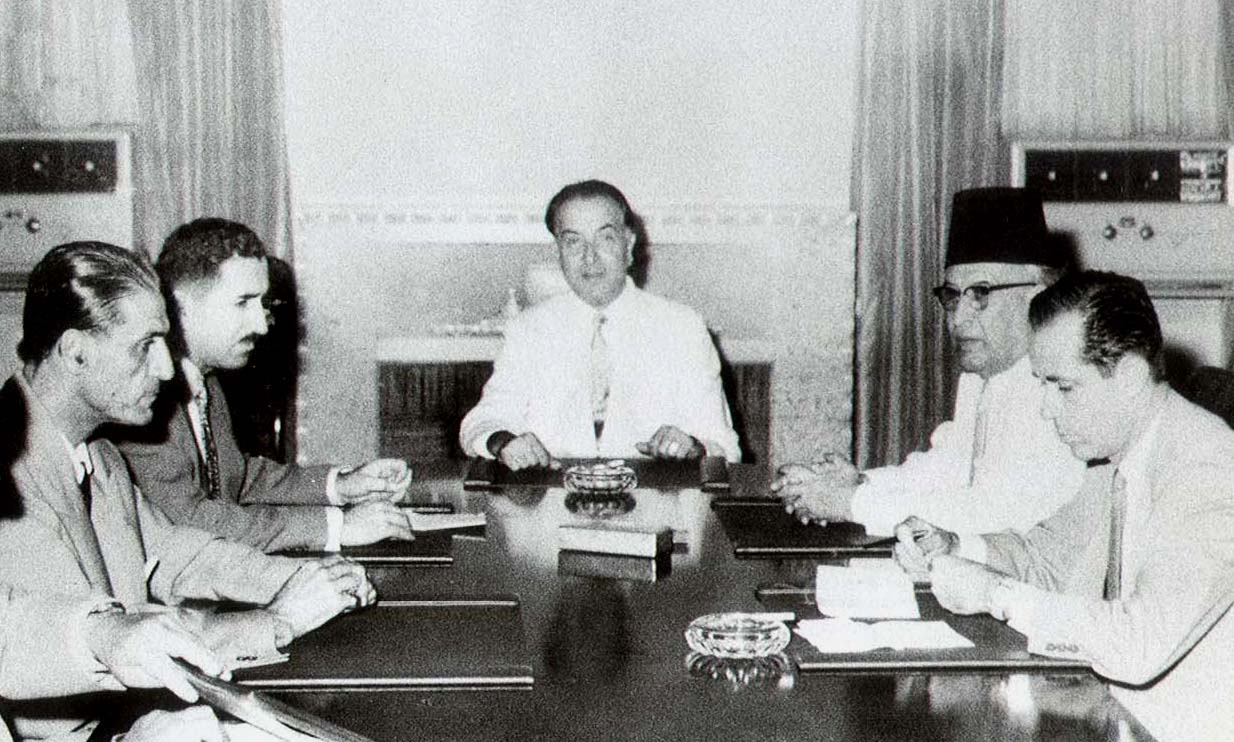

Upon his election, Chehab decided not to move to the presidential palace that was used by his predecessors in Beirut (Kantari palace). He chose instead to renovate a simple villa in Sarba, a five-minute drive from his house in Jounieh. His house remained his living quarters, while the Sarba ‘Presidential Palace’ was the ‘working place’, where he came daily from 8:30am to 3:00pm to hold official meetings and carry out presidential protocol duties. He had a late lunch with his wife when returning home, and went through the official mail, the summaries of local and international newspapers, and reports throughout the afternoon.

Wednesdays were dedicated to the weekly Cabinet meeting as well as meetings with ministers; Thursdays to meeting the governments General Directors and the experts in charge of studying or executing the various reform development projects, with whom he discussed these projects extensively; Fridays to meeting diplomats.

During summer time, he moved with his wife to a rented house in Ajaltoun, and would come down to Sarba only once or twice a week, keeping his regular weekly schedule and holding his other daily meetings in Ajaltoun.

Principles of Chehabism

Chehabism as applied by President Chehab was based on the following main political principles:

1- Protecting Lebanon’s independence and sovereignty

This was most exemplified in the following two significant events:

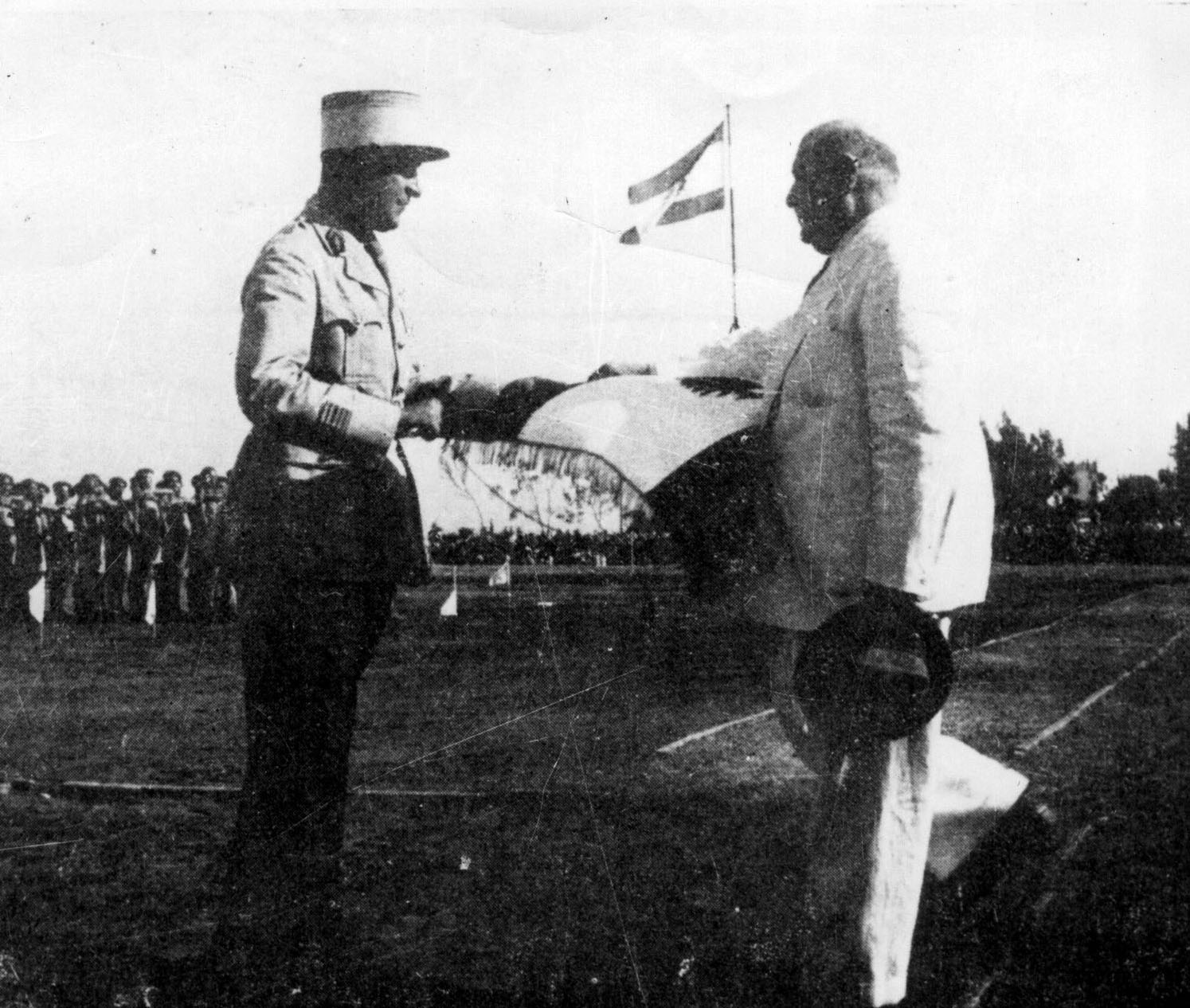

In 1958, when the Marines landed on the shore near Beirut and Chehab as a Commander of the Army was not officially informed: He gave orders for the Lebanese Army to aim its fire towards the foreign invading forces, the tension was diffused only after an official contact was established between the Marines command and the Lebanese Army based on restricting the deployment of the Marines to a limited coastal area near Beirut (Khaldé), without entering the capital.

In 1959, when he insisted that his summit with Abdel Nasser be held on the Lebanese-Syrian frontier.

In general, his pride for sovereignty was visible in his strong aversion to the major foreign embassies’ customary interference in internal affairs.

2- Preserving the National Unity

The 1943 National Pact, the unwritten constitution for the Lebanese political regime proclaimed on the eve of Independence, was the founding stone for President Chehab’s government. The Pact established Lebanon as a final united nation for all Lebanese (Christians reverting from seeking French sponsoring and Muslims desisting from their pull towards a union with neighboring Arab countries). When Chehab was elected in 1958, the basic elements of the National Pact were shaken, and Chehab’s task was to rebuild trust, heal the cracks and renew the Pact’s spirit. He succeeded in this and worked on re-strengthening this national bonding, internally by initiating judicious reforms and development projects, and internationally by repositioning the country in a neutral spot vis-a-vis neighboring conflicts.

3- Respecting and protecting constitutional legitimacy, democracy and public freedoms

These principles were highly sacred for Chehab. It was a paradox to see an army man, save and protect a democratic parliamentary regime. If Chehab was to follow the trend of army generals in the third world countries, he could have taken over power already in 1952, or intervened for this purpose early in 1958 (before the expiration of Chamoun’s mandate). He also would have accepted to amend the constitution for his re-election in 1964.

But instead, he remained intransigently faithful to ‘the book’ (the constitution) and the spirit of democracy that he deeply believed in. Often in his speeches to army officers, he would repeat the ideal that he asked them to strive for (and he was a living example of that ideal): To take it as a military duty to protect democracy and the parliamentary regime.

In regard to freedoms, he refused during his mandate two law projects proposed by members of the parliament aiming to limit the press’s freedom: a law to control the income of media and a law to limit the number of newspapers.

4- Keeping a balanced Foreign Policy

To best protect the National Unity and immunize it against situations similar to that of 1958 that would seriously shake it, Chehab followed a balanced foreign policy. He maintained friendly ties with the West, without being hostile to the Soviet Union. With him Lebanon assumed fully its Arab identity and took a neutral stand in regard to any inter-Arab conflict, encouraging solidarity (especially in regard to the Palestinian cause) and ‘brotherhood’ towards all the Arab countries. By this clear policy, Chehab succeeded in getting Nasser to respect Lebanon’s sovereignty and independence.

5- Political and administrative confessional balance

The Lebanese constitution states that the confessional regime running the country’s political and public life is temporary. The aim was to eventually replace this confessional consensus with a true democracy were the national belonging makes all Lebanese equal in rights. Chehab knew that this was still a far reached goal, and strove in the meantime on applying a fair confessional balance both in political life (representation in ministerial cabinets, essence of election laws), and in the public and administrative nominations. He applied the 50% Christian-50% Muslim rule, trying to introduce a few technocrat public figures to temper the strict confessional aspect in public life.

6- Social justice, nation-wide development

Social justice is the economic expression of national unity. Chehab rectified the social and economic injustice endured by the citizens in the remote regions, first by ensuring that basic needs such as schools, medical dispensaries, roads, electricity and water, reached them; then by introducing development projects in these regions. He believed that when the rights and needs of citizens were secured by the state, the confessional and regional allegiances of these citizens would slowly melt into a unified national identity, in which all Lebanese would enjoy equal rights and duties.

7- Economic liberalism and development planning

Chehab protected the free and liberal economy system enjoyed in Lebanon, making sure that the elements of personal initiative, free capitalism and bank secrecy remain protected in Lebanon’s economic system. But, following the examples of European countries, he introduced proper and long-term judicious planning into development (based on the expert studies provided by the IRFED Mission). This resulted in more stability, less control by monopolies, and an impressive economic boom and prosperity benefiting all the sectors of the Lebanese society.

8- Limiting foreign interferences in internal affairs

To curb the inherited and strongly embedded tendency of politicians to seek and strengthen individual ‘special relations’ with foreign powers, and as a necessary step following the coup d’état attempt of 1961, Chehab strengthened the intelligence services in the country (mainly what came to be known as the ‘Deuxième Bureau’). This succeeded in limiting foreign interference and ensuring security. But eventually this firm security grip was used as a tool by the traditional politicians who saw their power positions diminish, to criticize Chehab’s rule, accusing it of infringing on public freedom and democracy.

The Deuxième Bureau

After the 1961 failed military coup, there was an imperative need to reinforce the National security services in order to monitor existing foreign intelligence and minimize foreign interferences in internal affairs. Commonly referred to as the ‘Deuxième Bureau’ or ‘Second Bureau’, the Army’s Intelligence Service was restructured and given additional powers. President Chehab personally and carefully chose the officers for this service. Reviewing their military files, he picked young officers from modest and non-politically aligned families, having the Army’s culture of National belonging and public interest strongly embedded in them.

From 1960 to 1970 the Deuxième Bureau established a rare and precious prolonged period of stability and security, which allowed the country to enjoy a whole decade of prosperity and development. It was naturally disliked though by some traditional politicians who accused it of interfering in parliamentary elections to support new political figures, favorable to the Chehabist reforms, and of curbing the powers that the traditional politicians enjoyed, mainly through their well knitted ties with foreign powers. A masterfully directed campaign was thus waged against the Deuxième Bureau through the media, accusing it of controlling the political scene, even of ‘militarizing’ the country.

Early on in his mandate, faithful to his strong democratic beliefs, President Chehab had refused to pass a law that would control the sources of income of the media. Exploiting the sacred ‘freedom of press’, the politicians whose interests were hampered by the Chehabist reforms and the Deuxième Bureau’s presence, used the media establishments that they controlled to build a public opinion hostile to Chehabism, targeting primarily the ‘Deuxième Bureau’s men’. This reached its peak during President Helou’s mandate.

After Elias Sarkis lost the 1970 presidential elections, the same politicians, then in power, had a free hand to revengefully punish these officers and other officers close to President Chehab. First, the officers were removed from their positions; then they were assigned as military attachés to remote countries (India, Pakistan, South America, etc.). Only the head of the Second Bureau, Colonel Gaby Lahoud, was allowed to be in a European capital: Madrid. In 1972, the former Deuxième Bureau officers were called back to face a Military Disciplinary Council for ‘abuse of power, misconduct and embezzlement’, and in 1973, they were rushed into trial at the Military Court and dismissed from the Army. To avoid being thrown in jail, Lahoud had to seek political asylum in Spain while others did the same in Syria. Late in 1974, the court sentences were reversed, the officers were acquitted from all accusations, reintegrated into the Army and their military ranks and rights were fully restored.

Today, there is a universal appreciation and praising amongst all Lebanese groups and journalists for Chehab’s views, the remarkable achievements of his mandate and his sincere endeavor towards building the State of institutions, but there is still a trend amongst some journalists to criticize the Deuxième Bureau, accusing it sometimes of even having had a grip on Chehab himself!

The fact is that these officers, entrusted with extremely sensitive responsibilities, were fully committed to serve Lebanon’s national and non-sectarian interests, free from any personal interest while executing their duties. With this resolve, though with limited resources, they blocked all influence of foreign intelligence on the Lebanese territory, monitored the ties and connections of public and press figures with outside powers, and had full security control on all happenings within the borders.

They were, like all the officers of his close team, the people that Chehab trusted the most for their integrity, honesty and professionalism, and towards whom he showed a true fatherly affection. He was extremely affected by the vengeful unfairness that they suffered after 1970, kept a personal correspondence with each of them when they were sent to far countries and was deeply concerned for their future and their families’ living conditions. His wife maintained this attitude after his tragic death in 1973, repeating to many that the main cause for the President’s fatal heart attack was his deep sadness for the way in which those officers were unfairly prosecuted, and how this would affect the Army and its morale in the future, and thus Lebanon’s precarious stability and its immunity against foreign interferences.

Challenges of Chehabism

What can be identified as limitations to Chehabism on the practical level, are in fact fundamental principles of the Chehabist thought: Respect of democracy and the constitution, introducing changes only when citizens are ready for them, not using propaganda to manipulate people’s feelings and dreams.

Chehabism’s golden era was President Chehab’s mandate years (1958-1964). To prolong this era and move forward with the reforms, Chehabism needed to stay in power longer. But in 1964, truthful to his principles and out of respect to the constitution, Fouad Chehab refused to run for a second mandate,which would have allowed him to powerfully continue with the state reforms and the development projects. He chose to back Charles Helou, a civilian, to continue the mission. President Helou, started his mandate following in the footsteps of Chehab’s reforms, but slowly fell into the traps of politics and compromise between matters of pure national interest and others of political maneuvering nature. This made the retired Chehab distance himself from Helou, and Helou engaged in subtle power struggles with other Chehabist strong components: politicians and members of parliament faithful to Chehab, and most of all the ‘Deuxième Bureau’, which enjoyed a powerful and respected presence.

In 1970, and despite the insistence of the parliamentary majority, Chehab chose again not to run for presidency, endorsing instead his ‘spiritual son’, Elias Sarkis (who unexpectedly lost these elections by just one vote). As expressed in his statement of August 4, 1970, which explained why he didn’t want to run for presidency again, Chehab believed that the country was not yet ready for the changes that he would never consider imposing by non-democratic means.

Probably because of a personal sensitivity towards the fascistic ways that Europe had recently endured, and the military regimes in the Arab world, Chehab had a strong dislike for the use of propaganda or the creation of a public idol image around his person.

The limits of Chehabism can be summarized in one condition that Chehab had put: That all citizens participate with conviction in the national reform task.

Chehabism after Fouad Chehab

Being a way of governance, Chehabism in theory can be envisaged without the personal presence of Fouad Chehab. But the post-1970 period – and up to date – has shown that without Chehab (and the respect that he personally imposed), and without the special conjuncture that brought him to power, Chehabism never fought to reach power again. Also, when it did reach the presidency through national consensus when the nation was facing dead-end situations, Chehabism did not have the opportunity or the means to take initiatives.

Elias Sarkis, Chehab’s personal presidential choice for 1970, was elected by consensus in 1976, but the deteriorating situation in the country left him with no political authority and no chance to even envisage reforms or development. For six years, all that he could do was manage the crisis, try to minimize the damages, and protect the little that could be preserved of the State’s presence.

In 1989, after the Taef agreement, when looking for a personality accepted by all and could successfully reunite the country and govern it in a healthy way, the choice fell on President René Moawad, a devoted and committed Chehabist politician. Unfortunately, Moawad was killed before he even took office or started his nation-rebuilding task.

In 1998 and in 2008, when searching for a consensual President with the profile of someone able to reunite the nation, the choice fell on the Commanders in Chief of the Army General Emile Lahoud and later on General Michel Suleiman, inspired by the choice of General Chehab in 1958.

This leads us to conclude that Chehabism, with or without Fouad Chehab’s presence, does not live on adversity or seek power. It is called upon in a time of crisis, and takes over authority on a national (and international) consensus basis. Thus, Chehabism never envisaged forming a political party nor competing with other parties for positions and public responsibilities.

Nevertheless, Chehabism is undoubtedly a virtuous way of governance that any person in a responsible position can be inspired by and can seek to apply when approaching matters of general interest, particularly delicate ones.